Caught Between Two Rutting Bulls, From the Archives

This story, Double Trouble, originally appeared in the September 1998 issue of Outdoor Life.

SOMETIME EARLIER that afternoon I had given up. My aching muscles and discouraged spirit signaled the end of the hunt. I would keep my eyes open on my way back to camp, but that’s about it. As I approached the ridgetop, I found myself at the exact location from which I had first bugled that morning. An omen? No, I don’t believe in them. However, my legs needed a break, so why not bugle while I rested? I positioned my favorite diaphragm call in my mouth and let out a clear, clean, four-pitched melody that echoed into the valley.

This area, “The Gorge,” was appropriately named for its steep narrow canyons and deep-cut ravines. The lodgepole pine forest contained thickets, benches, downfall, and undergrowth. The conditions that made this area difficult to hunt were the primary reasons why the elk were there. It was some of the finest elk habitat I had ever encountered, a true “bull hole.”

I thoroughly enjoyed this hunt without a client. Seldom can I get out by myself and hunt the way my father taught me – tracking along at my own pace, knowing just when to slow down or stop, constantly studying the forest for signs of elk, and balancing aggression with caution. There is something about hunting alone that fulfills a special need.

After 15 minutes of complete silence from my spot atop The Gorge, I stood up and prepared to offer another challenge. Fog had moved in, transforming The Gorge into a haunting sea of emptiness.

My piercing call seemed absorbed by the heavy moisture, trapping even the echo. I resumed my position, then stretched out flat to relieve the back and shoulder pains that had accumulated during the hunt. Snowflakes settled on my face. Snowstorms in Colorado’s Rawah Wilderness can be expected almost year-round, but it had been a bit unusual in that it had snowed 7 of the 14 days this muzzleloader season. However, the storms seemed to encourage the elk to use their full vocal repertoire.

Another 15 minutes passed, and with it a third unsuccessful bugle. I kept tracing the design of new scars on my gun stock. A fall had damaged the finish I had worked so long to achieve. It didn’t matter now, and my carelessness served as a reminder of how quickly and easily things can turn unexpected out here in the woods.

I tried to think of other places to hunt, but just couldn’t get excited about moving. The Gorge was the only place I’d found Solomon that year. The other guides and I had given this bull the nickname after years of being humbled by his wisdom. One of the benefits of spending extended time with elk is coming to know the individual animals – their habits, patterns, sizes, and offspring. Solomon usually separated himself from any herd in the area, even during the rut. Periodically, he could be found keeping company with one other bull, which we called Broken Toe. We speculated that Broken Toe might be Solomon’s father or a mentor who had raised him after his mother was killed.

A clap of thunder rolled past me and I instinctively bugled at the sound. I had heard elk do this and thought it might add credibility to my calls. A barely audible response rose from The Gorge. It was best to start off slow.

A few minutes later I bugled again, stimulating a quick rebuttal. With each successive exchange, the chorus added another member, until the air was filled with a continuous melody of bugles, grunts, cow/calf calls, whistles, and chuckles. Two separate herds mingling had greatly confused the numerous raghorns that year.

It was getting dark and time was running out. I chanced another bugle, knowing it might simply scare everything away.

I tried to identify all the participants, but it was impossible. Satisfied that Solomon’s voice was not among the chorus, I was content to listen for the last hour of the season. As I relived the events of the past two weeks, an unmistakable scream brought me to my feet. After replaying my recordings of Solomon so many times, I thought I’d be able to pick him out anywhere. Then, with his second bugle, there could be no mistake. I found myself running and sliding down the hillside. Did I remember my gun? Yes, it was in my hand. My grunt tube? Still around my neck. Except perhaps common sense.

The thickest area of downfall was directly below. Knowing I wouldn’t have enough time to work around it, I pushed straight ahead toward the source of the bugle. Any attempt to be quiet would be futile. As I emerged from the dark timber, the bugling ceased. I estimated the elk’s location and proceeded cautiously, hoping not to be spotted. Several bulls were now within range, disappearing then reappearing in the fog. I couldn’t compromise my quest now with a lesser animal. I continued to answer each of Solomon’s challenges with an exact imitation, hoping to irritate him enough to make a mistake.

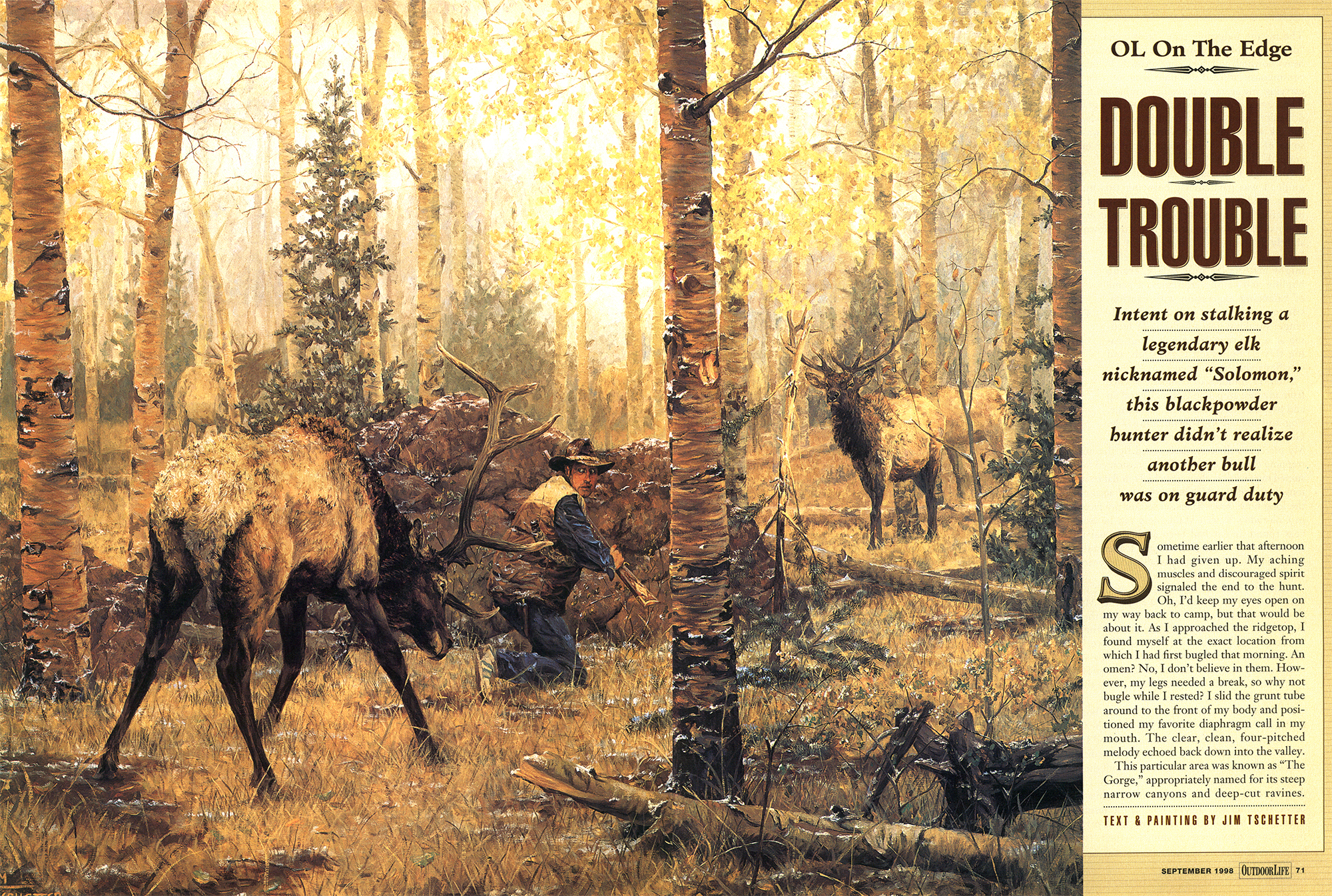

One bull charged at another, clacking their horns in the distance. Most of the elk were just standing around listening, much like me. Suddenly, there he was. Solomon’s heavy horns swayed back and forth as he approached. I prepared to shoot, but then a crash behind me commanded my attention. Broken Toe had flanked me and was charging. I pushed backward and fell to the ground, just managing to avoid those long tines by inches.

The enraged bull spooked as he thundered past. Regaining my senses, I turned and checked for Solomon. He was walking away, but probably still within range. However, the trees were too thick for a shot. I surveyed in front of Solomon, searching for openings. As his light-colored body entered the narrow gap I’d selected, tree limbs I hadn’t noticed came into focus. And now his body was angling away, leaving few vital areas exposed.

Over the years I must have said to a hundred clients, “Don’t always count on a wide-open broadside shot … sometimes you have to take what’s available.” Well, sometimes you also have to pass on a bad shot. The only thing more disheartening than letting him go was the thought of a wounded Solomon running off to die, only to be eaten by coyotes. A hunter can only do what his standards will allow. In stately, unhurried grandeur, Solomon moved off. I can only think to meet up with, and to thank, his bodyguard.

Epilogue

A few years after my encounter with Solomon and Broken Toe, we did finally catch up with the latter. Broken Toe was approximately 15 years old at the time. One of my archery hunters claimed him as a trophy after yet another two-hour bugle session.

Broken Toe’s rack was unique, with three separate bases and antlers on his left side. Solomon was never seen or heard again. It’s very unlikely such a bull could have been taken and not recorded, so it’s safe to say he continued to outsmart everyone for the remainder of his natural life. In either case, Solomon and Broken Toe live on in our memories as we recount our experiences with them each hunting season.

Jim Tschetter is the head guide for North Park Outfitters in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. He has been depicting his experiences on canvas for decades.

Read more OL+ stories.

A skilled hunter, dedicated conservationist, and advocate for ethical practices. Respected in the hunting community, he balances human activity with environmental preservation.